OUR HOLLYWOOD HISTORY (7/10)

The movies have always had a love affair with "Bad Boys". Fans love rugged, hard-living, hard-partying characters who break all the rules, get all the girls and somehow end up on top.

Sometimes it works in the studios' interests to imply that the actors playing those parts aren't far removed from the characters they make famous.

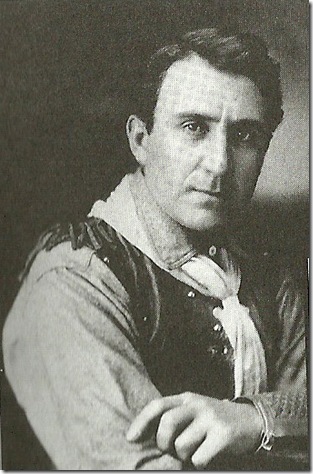

The stories about Errol Flynn, Sinatra's "Rat Pack" and other stars up to and including Charlie Sheen have become the stuff of Legend. But one man can be credited for not only creating the myth other stars have emulated but embodying it completely, a Canadian named Jack Pickford.

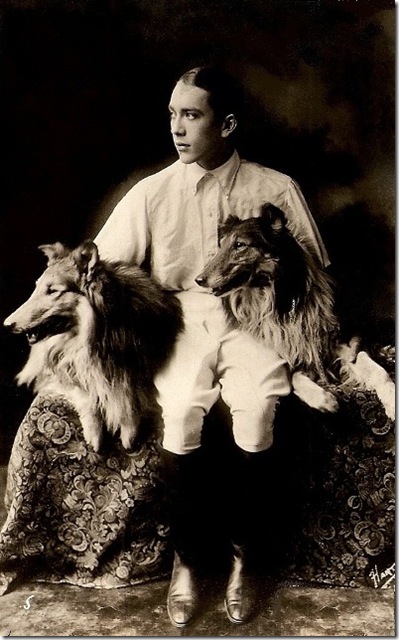

Pickford was born in Toronto on August 18, 1896, the youngest brother of Mary Pickford, who would become the biggest star of the Silent Era. But while she became beloved as "America's Sweetheart", with more fans than the rest of Hollywood put together, her brother solidified a reputation as "Hollywood's Nightmare".

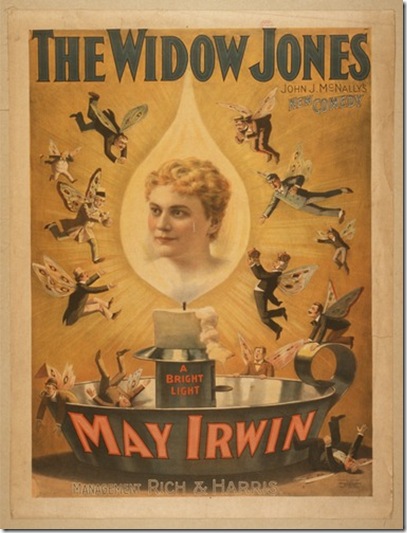

Jack made his stage debut at the age of 8, universally acknowledged as a beautiful boy with immense talent and predicted to follow in the footsteps of his already famous (in theatrical circles) sister. Some even felt Jack had the makings to become the best actor of his generation.

But somewhere during the run of his very first play, Jack revealed another side of his personality, one which would soon scandalize not only the movie business but much of the world -- and ultimately destroy him.

Later in life, Jack acknowledged that his legendary capacity for alcohol got its first test during that first play. And it ignited a desire to push the boundaries of morality as much as he could.

Even as a child, Jack had an unbridled love of fun. He was known for possessing a potent combination of talent and charm. He was nice to everybody, a completely "happy-go-lucky" guy. By the age of 12, he was wowing Broadway audiences and producers. As one director put it, "He came over the footlights like an angel from heaven."

But backstage, another Jack Pickford was emerging. His sense of fun warped into rough practical jokes that humiliated members of his casts and crews. At the age of 13, he was caught having sex with the daughter of a wardrobe mistress. He once even glued on a merkin to hide his youth and visited a whorehouse. The merkin didn't fool anybody. But it did make him a hit with the resident ladies.

Those incidents aside, his drinking increased exponentially and he began using cocaine. Audiences still loved him, but he was becoming a handful backstage.

His mother enrolled him in a military academy in the hope he would straighten out. But instead, Jack recruited other boys into what might have been show business's first "entourage". When one theatre owner attempted to discipline him for some prank, Jack had his academy friends descend on the theatre and cover it with obscene graffiti.

Before his 14th birthday, he was officially blacklisted by the New York Theatre Managers and Producers Association -- forbidden from even attending auditions.

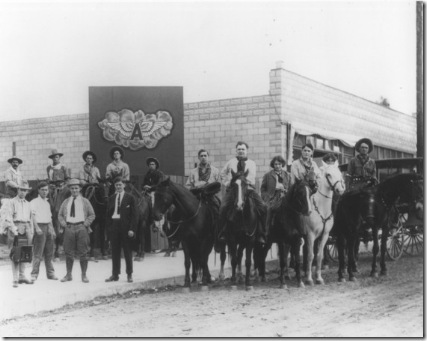

Jack's banning didn't have much impact, however, for in 1911, the entire Pickford clan moved to California to embrace the movie business fulltime, and producer Carl Laemmle, perhaps unaware of Jack's excesses, perhaps hoping to curry favor with Mary, signed him to a movie contract.

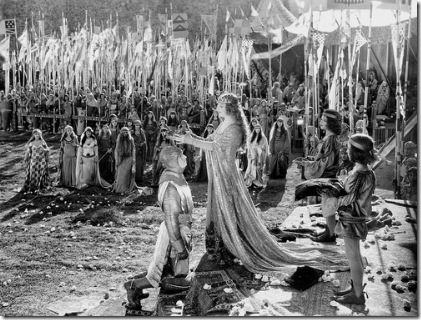

A year later, at 16, he starred in his first feature, "A Dash Through The Clouds", while also causing a lifelong rift between Mary and fellow silent stars Lillian and Dorothy Gish by -- as Lillian would admit decades later "doing things to Dorothy that neither of us understood at the time".

Indeed Jack had a reputation for turning up in the dressing rooms of his leading ladies, dropping his pants and ordering them to have sex with him. Some threw him out. But many more did not.

Jack also formed a new entourage that included actors Wallace Reid, Lew Cody and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle. They were known for their wild parties and out of control hi-jinks. First dubbed "Pickford's Gang" and then "The Rat Pack" they were rumored to be regularly provided with cocaine by director Desmond Taylor -- until he was mysteriously murdered; and once literally destroyed an exclusive Beverly Hills country club.

Banned from ever darkening the doors of the club, Pickford and his pals crashed a car into the main dining room, tossed patrons into the pool and then pelted them with beer bottles. Mary somehow managed to convince the police to drop charges and paid for all the damage.

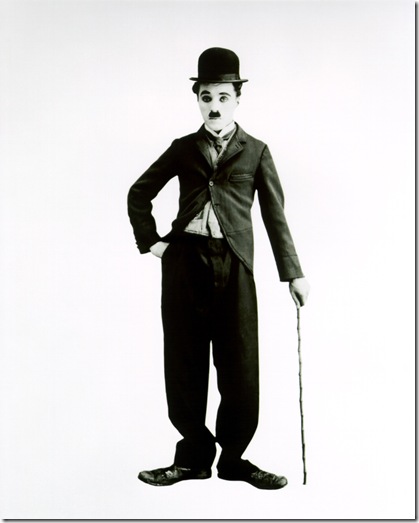

But Pickford's gang had some harmless fun at the expense of other stars as well. On Charlie Chaplin's wedding night, they hired the famous Paul Whiteman orchestra to set up on his lawn and play Sousa marches into the wee hours. Despite Pickford's assurances that Chaplin was in on the gag, he wasn't around when the police arrived and hauled the entire orchestra off to jail.

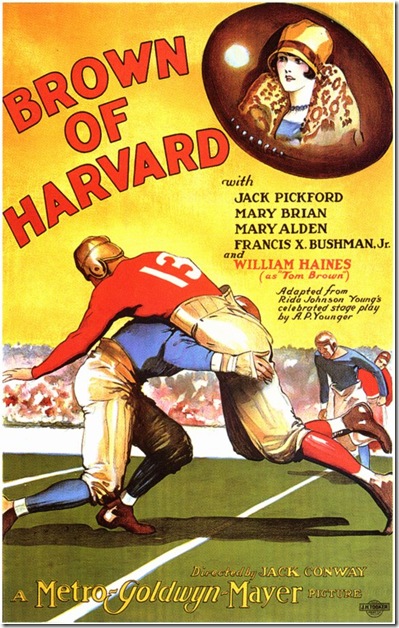

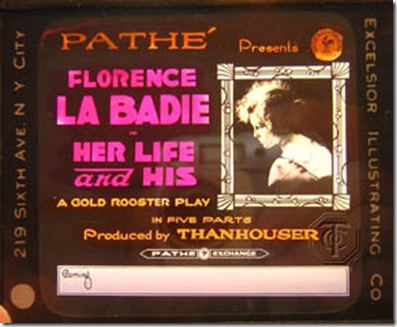

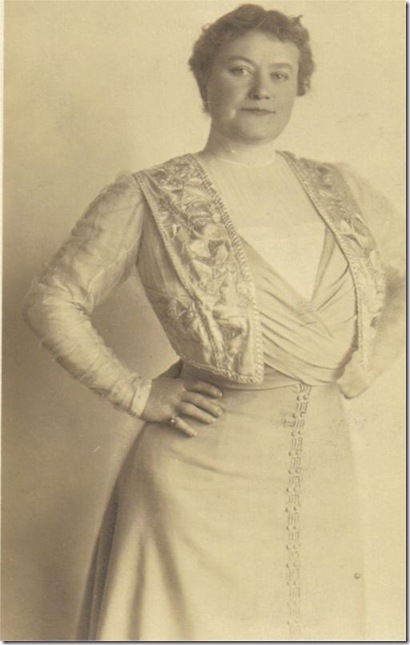

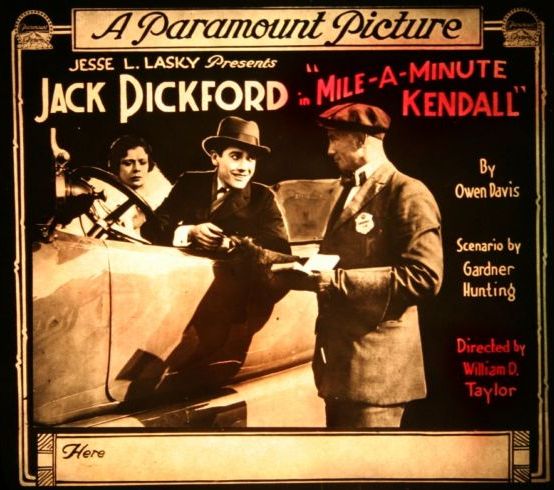

As Pickford's career success grew with movies that were lauded by critics and hugely profitable to the studios, so did his capacity for causing trouble. He appeared to be settling down in 1917, after Paramount's Adolph Zuckor provided financial backing for the independent "Jack Pickford Film Company" and he married Zeigfeld Girl and rising star Olive Thomas.

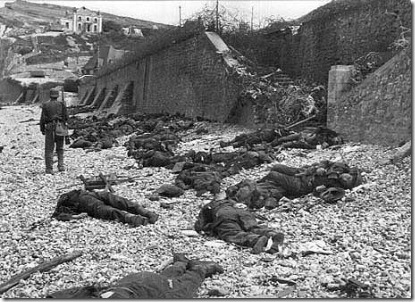

But with America entering WWI and realizing he might soon be drafted, Jack suddenly enlisted in the Navy. While studio publicists applauded his patriotism, privately, he told friends his fame had allowed him to land a cushy desk job far from any combat.

And to all outward appearances, Jack seemed content to serve his country although stationed in New York. But shortly after the Armistice was signed, the New York Times ran a headline screaming, "Scandal in the Navy" over a story revealing that Jack Pickford had been supplying women, booze and a penthouse party location to Senior officers in order to secure safe postings for friends and wealthy associates.

A little studio and family finagling saved him from a court martial and although discharged as "medically unfit to serve", Jack was soon back in LA making movies. But Olive was heart-broken at the realization that the man she'd married had not mended his ways.

The couple seemed headed for divorce. But a year later, they set sail for a "second honeymoon" in Paris. Unfortunately, it would end in tragedy.

After a night of clubbing in Montmarte, Jack frantically called the front desk of his hotel to send up a doctor. A half hour later, Olive was pronounced dead -- from poison.

At the inquest, it was revealed that Jack had been diagnosed with Syphilis in 1917 and was taking the only known medication at the time, Bi-chloride of Mercury -- poisonous in large doses. Shortly after his return from the Navy, Olive learned that he had passed the incurable disease to her. To this day no one knows if her death was from an overdose of Mercury, suicide -- or she was murdered to keep Jack's secret.

Back in Hollywood, Jack had become a pariah overnight. He only made one film in the next year, albeit with a clause in his contract that he would have no physical contact whatsoever with his leading lady.

He soon left town for New York, returning a year later with a new bride, another Ziegfeld girl, Marilyn Miller. Ziegfeld was outraged, threatening in print to "murder the man". But once again, Jack charmed Hollywood's elite and appeared to be mending his ways.

The newly remarried Jack was affable and agreeable with everyone. Over the next couple of years he made eight more successful films. On the surface, his domestic life seemed perfect. Yet as one close friend confided, "That's the thing about Jack. He's always pleasant. But he's always loaded."

Then one day, Marilyn announced that the marriage was over and returned to New York to take the lead in a new Ziegfeld show. After five years of marriage, she had finally learned her husband had Syphilis.

A deflated Jack made one last film, "Exit Laughing" and then joined Marilyn in Paris to finalize the divorce. Why Paris? The couple knew a divorce in New York or California would require them to provide details of their marriage neither wanted to make public. In Paris, they were out of court in 20 minutes.

Jack dropped out of sight for a while, surfacing in the social pages in 1930 when he married a third Ziegfeld girl. A year later, she too learned of his disease and moved out of their home.

Pickford then drifted back to California, now suffering the dementia that accompanies the final stages of Syphilis. After visiting a friend in Palm Springs in 1931, he missed a curve while speeding down a desert highway, totaled his car and was badly injured.

Mary rescued him from the small hospital to which he was taken and placed him in a private clinic in Los Angeles, where he was soon declared "clinically insane".

Jack's days in the clinic were mostly spent singing dirty songs as he recovered from his physical injuries. Once those were healed, however, he often became violent and Mary finally had him transferred to a clinic in Paris that claimed it had found a cure for Syphilis.

But recovery was not in the cards for Jack. He died on January 3, 1933, an autopsy revealing that much of his brain had been eaten away.

Hollywood's first "Bad Boy", a Canadian, was finally at rest.