This has been a bad year for losing the friends and acquaintances who were around when I started my career. So far, the count is 13.

Somewhat to be expected when you edge past your 50's. But it's more than the number of soldiers we lost in Afghanistan this year. And yet I don't hear Michael Ignatief or Jack Layton calling for a withdrawl of Canadian artists from the Quagmire of Mainstream Media and negotiating a truce with the American TV and Film hegemony.

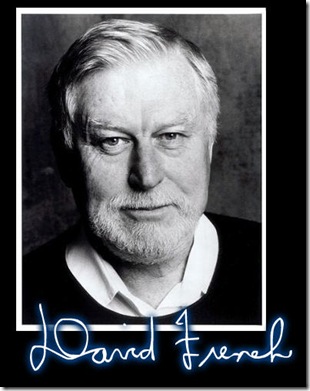

Already saddened by the weekend passing of playwright David French, I took another hit opening the newspaper to his obituary and finding another for film professor John Katz. And then, just a few hours later, the news that the voice of CITY-TV, Mark Dailey, had died was being posted online.

At best, only one of those names will register with any given group of Canadians, if they register at all.

If you're a fan of Canadian theatre, you might recall French as one of its early icons.

If you love movies, you might've read one of Katz's books on that medium or caught a film he programmed for some festival.

If you lived in Toronto you were likely aware Dailey anchored a newscast or made an effort to tune into a "Late, Great Movie" in time to catch his inimitable introductions.

Those who knew of all three might well think they didn't have much in common. But they did.

In a lot of ways, they were the same guy walking separate paths through the same point in space and time along a portion of Toronto that's come to be known as the Mink Mile -- and walking it with a purpose.

I don't know who coined the term, but "The Mink Mile" describes a section of Bloor Street in Toronto that stretches West from the city's official center at Yonge Street to a residential neighborhood known as the Annex.

The Mile's first blocks are filled with exclusive stores, the town's version of Rodeo Drive. Then comes the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto Campus before a stretch of funkier stores, beer joints and coffee hangouts that service the Annex's resident students, artists and downtown movers and shakers.

When the city birthed an explosion of Canadian theatre in the early 1970's, most of the theatres were in and around the Annex. It had a freer campus vibe. Beer was still 15 cents a glass at the Brunswick House and big old homes that would later be gentrified were cheap rooming houses and crash pads.

The summer I hit town, Bill Glassco's Taragon Theatre, which would become one of the our most respected, had its first hit with David French's "Leaving Home".

Better writers than I'll ever be have penned thousands of pages on what that show meant to Canada and Canadian theatre. It was basically our "Death of a Salesman" -- only more heart-rending. I had the good fortune of seeing it with the original cast, with bravura performances by Sean Sullivan and Frank Moore in the classic generational battle of father and son.

The play's emotionally shattering final scenes remain a testament to the power of theatre.

Back then, and really for most of the rest of his life, David was a fixture on the Western end of the Mink Mile. I never did one of his plays, but I worked a couple of shows at the Tarragon where he was writer in residence for a while. And he turned up at everything else that played in town, often by himself, always way in the back and usually leaving without saying much to anybody connected to the show.

But I lived in the Annex and would see him from time to time grabbing coffee in the morning or walking Bloor street late at night eternally lost in thought. We'd nod a "Hello". I'd compliment him on something else he'd written and he'd offer kind words about whatever I was doing.

Now and then we'd both have seen a show neither of us had anything to do with and discuss it over a cup of coffee. My reactions were those of an actor, his were the ones that writers have.

But he'd started out as an actor too and had written for TV long before he became a revered playwright with a play now included in the Oxford Dictionary's list of "Essential English Drama". Not bad for a guy who started out writing monologues for Howard the Turtle on "Razzle Dazzle".

What I recall most was how passionate he was about the theatre. Whether it was accurate or not, I got the sense he didn't think he was all that special, but the success of one show had put him in the spotlight and he wanted to make sure he didn't disappoint. He always gave me the feeling that if something he did wasn't dead, solid perfect it would let the whole Canadian Theatre scene down and he wouldn't allow that to happen.

John Katz hung at the other end of the Mink Mile, near ground zero of the Film Festivals he helped program and the offices of the fly-by-night producers who fed off the nearby bankers and lawyers and old money while fueling the break-through of a Canadian film industry.

John had a completely different personality from David French. He was outgoing and ebullient and effusive, always on the move and talking a mile a minute. He'd button hole complete strangers after a screening, not to get their opinion, but to make sure they'd loved it as much as he did. And he wouldn't let them go until they promised to tell their friends and make sure their friends told friends.

He never seemed to stop sparking people to do something to promote or further the film business. He wrote books about films, he taught filmmaking at York University and he scoured the world to find great films he could introduce to his homeland.

In 1979, he programmed Ira Wohl's documentary "Best Boy" for Toronto's "Festival of Festivals" and when it didn't find a distributor bought the Canadian rights himself. It went on to win the Academy Award.

Around the same time, he wrote the first of two books on documentary filmmaking, "Image Ethics" about the responsibilities of those in the film world when they make public the private lives of ordinary people.

It's the kind of book those making most of what passes for reality on Canadian TV completely ignore.

But others did not and many who took John's courses at York University would go on to win Academy Awards and other cinematic accolades of their own.

"Image Ethics" became a seminal work in establishing the Media Ethics Association and it led to required courses in most North American schools of media and journalism.

But John was also often found in the trendy eateries of the Mink Mile and his love of film and writing skills got him into a few script and story deals with the Canadian movie moguls who habituated the same locales.

We'd often talked about movies. But one night he phoned because one of those moguls was "screwing him around" and he needed some advice. I helped him as much as I could. And I guess it worked out okay. Because a few months later, he sidled up to me at a screening in his trademark white suit, pastel shirt and loud tie to whisper a quiet "Thank you". It was the only time I ever heard him speak in a hushed tone.

A little over a decade ago, John's reputation as a teacher and the academic success of a couple of his other books landed him a job teaching at Penn State, where a new generation of film students were entertained and inspired by lectures that would continue until mere days before his death.

Like John Katz, Mark Dailey was a transplanted American. He'd started his professional career as a cop in Ohio, but gave that up to report on crime in Detroit and eventually brought his act to Toronto and a seat-of-its pants news department at CITY-TV.

Mark became a well known face up and down the Mink Mile and pretty much every other street in the city. While other reporters did their stand ups from crime scenes in a suit and tie, Mark showed up in a trench coat and fedora, like some ink stained wretch from an old Dan Duryea movie.

His voice soon became synonymous with CITY-TV, delivering breaks and bumpers and program introductions in a breezy, refusing to be impressed style that gave the impression the guy was on the street 24 hours a day. He was the reporter who never stopped dogging a story and didn't give a shit if you didn't like how he told it.

If you search Youtube, you'll find dozens of intro's Mark voiced for CITY-TV's "Late Great Movies", most of them pointing out that the film was far from great, starred people nobody had ever heard of and often included spoilers like "Tonight you'll see the guy who now signs my paycheck get shot".

I first met him when he came to do one of those five minute bits on a new play opening in town. That was normally the turf of some young pretty who worked at the station. But I guess she was sick that week because Mark drew the assignment.

Given the location of the theatre, he might have just been nearby because somebody had been murdered in the back alley.

Most entertainment beat reporters doing that kind of thing turn up wearing fashions no real actor can afford and work from a press release because the show hasn't opened yet. Their first question while the videographer sets up is always "So, what's this play about?".

But Mark had attended the previous night's preview performance and asked the tough questions that most entertainment reporters think will either flummox the interviewee or their audience. Like everything else he did, he was a breath of fresh air.

Years later, our paths crossed again when he was anchoring CITY newscasts and I was doing ride-alongs to help make a cop show more true to life. Ever the reporter, he'd caught a call on his police scanner and decided it was a story that needed his touch.

It took a couple of minutes for him to recognize me in this new career configuration. But once he did he went on at length about how much he liked what we were doing, giving me a list of stories and local cops I should look up while also mentioning some he remembered from the mean streets of Detroit. I dutifully followed up and one of those Detroit stories made it onto the show.

What all three of these men had in common was how passionately they cared about what they did and the city they called home. Not that many others didn't or don't. But with David, John and Mark, it seemed to be a calling, something they had to do for all the others they passed as they made their way along the Mink Mile.

Each in their own way gave rise to something that, at one time, defined Toronto; its indigenous theatre, its scrappy film industry, its roving reporter who really was "Everywhere".

Often, when people die, someone will say that their work here was done. And that's a feeling I can't shake about so many of those I've lost this year. For while I know there are men and women of equal talent and passion doing the things that they did, it still feels like those who have gone left because Toronto and the Canadian entertainment world didn't need them anymore.

Canadian theatres are struggling to survive these days, especially if their plays are written by a Canadian like David French.

Despite a sparkling new theatre for Festival films that would have made the heart of John Katz leap with joy -- more people will see "Black Swan" during its opening week in Toronto than will see every single Canadian film released there this year in total.

Meanwhile, the TV station that Mark Dailey symbolized falters in the hands of people who think reporters need to wear suits and be eternally deferential and respectful to owners who only know how to imitate rather than innovate.

The Mink Mile is firmly back in the grip of the bankers and the lawyers and the old money that first established it. Not that it ever truly belonged to anybody else. But for a time, people like David and John and Mark made it feel like it was a place for everyone.

But now their work is done and its time for somebody else to step up before what they accomplished disappears forever.

No comments:

Post a Comment