OUR HOLLYWOOD HISTORY (9/10)

Virtually any respected encyclopedia, reference book or history of the motion picture will tell you that the first movie with sound was Warner Brothers' "The Jazz Singer", released on October 6, 1927 and that Al Jolson's "Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain't heard nothin' yet." were the first words spoken onscreen.

Like a lot of stuff that comes out of Hollywood, this is pure bullshit.

Because another "Talkie" had appeared months earlier using a process invented and perfected by a Canadian.

Douglas Shearer was born in Montreal, Quebec in 1899. And while his sisters Norma and (the unfortunately named) Athole aspired to be singers, actresses and models, he became obsessed with electricity.

Long before he was even in high school, little "Dougie" had built an electrical lab in his basement, alongside the darkroom he'd constructed, to conduct experiments in -- "the miracles of sound and light".

At the time, residents of the upscale Westmount neighborhood were constantly complaining to the city of frequent power blackouts. City workers were at a loss to explain them. And Shearer's parents never revealed that most were caused by their son's basement experiments.

Before he was 14, Shearer ditched school to work at Northern Electric, where he was soon a leading light in their experimental division. Eventually, with the help of a teacher who faked a high school diploma for him, Douglas entered McGill University to study electrical engineering.

But his family fell on hard times and after only a year of University, Shearer was back at Northern Electric.

Around the same time, Norma and Athole moved to New York, where both found theatre work and soon began appearing in films at Biograph. Norma was quickly singled out by Universal executive, Irving Thalberg, who brought her to Hollywood. By 1924, she was making quite a name for herself and Douglas decided to visit.

Thalberg was now second in command at MGM and he and Norma were engaged. At one of their parties, Douglas fell into conversation with Jack Warner, who offered him a job, "starting at the bottom" at Warner Brothers. The next day, Shearer went to work moving props.

But he spent his long hours hanging around the set learning all he could about the way the industry used cameras and lighting and began dabbling with ways of improving it. He discussed many of these over Sunday dinners at the Thalberg house and soon found himself invited to perfect his ideas for MGM.

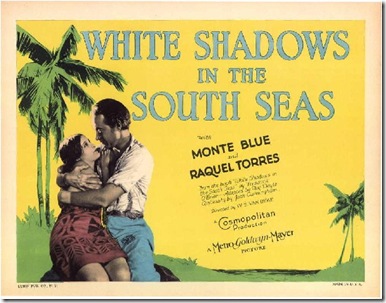

But while he tinkered with light grids and camera accessories, Shearer knew that the Holy Grail for all of Hollywood was Sound. And a few weeks after he'd arrived, he took a silent film, "White Shadows in the South Seas" into a recording studio and added music and effects that could be synchronized to the film by linking it to a phonograph.

Other studios had been supplying recorded music to play alongside their films for a couple of years. But no one had ever increased the reality of the experience by including the film's sound effects. Shearer achieved his single track record of both by creating sound effects while a live orchestra played the score.

Despite the film's success, Shearer knew what audiences really wanted was to hear actors speak.

In 1927, during the filming of Norma's next picture, "Slave of Fashion", he approached Thalberg with the idea of creating a talking trailer for the film. It would be a test run of his new Sound technique in all 15 Los Angeles area theatres where the film would play.

To create the trailer, he had the director film several scenes with the actors clearly mouthing their lines. Then after the film was edited, he had the cast lip-synch their dialogue as it was projected in a recording studio.

The dialogue was put on one disk and music and effects on another because no one had yet perfected a method of mixing all the sound elements together without one element drowning out the others.

But this meant that each theatre projection booth would need two additional people capable of dropping the needle on their separate records at the exact time the first frame of the trailer hit the projector.

Not confident that would happen, Shearer's plan called for a local radio station (where technicians regularly combined or "mixed" multiple recordings during live radio dramas) broadcast sound to the theatres. Radio speakers were set up behind each movie house screen with the projectionists taking their cue from the broadcast. It worked perfectly.

The "Talkie" had arrived.

In fact, the first screening was such a sensation, with audiences leaping out of their seats and cheering, that MGM had to arrange for an immediate repeat broadcast.

The trailer experiment went on for a week, with theatre managers claiming people were paying just to see the trailer and coming back every night.

But success turned to failure when "Slave of Fashion" was released. The finished film was still silent and audiences, led to expect much more, booed it off the screen.

Shearer was certain, however, that combining theatre showings with radio broadcasts could be accomplished for entire films. But MGM head Louis B. Mayer disagreed. If audiences could hear a movie in the comfort of their own homes, he reasoned that they wouldn't venture out to spend money to see it in a theatre.

A few months later, Warner Brothers released "The Jazz Singer", which, despite its "Hear Jolson Speak" hoopla, was a silent film with a musical track and only brief vocal interludes.

Shearer knew Hollywood had to think of something better. And he quickly did just that.

All over the city, studios were trying to perfect disc recording processes. But since film was fragile and constantly breaking, using such a system meant sound and picture were often completely out of sync.

Shearer felt the answer lay in magnetic tape and concocted a method whereby a second camera recorded sound while a primary camera recorded images. The process was tried for the first time with MGM's "All Talking, All Dancing, All Singing" feature "The Broadway Melody" in 1929. The film was a huge success and won that year's Academy Award for Best Picture.

Still feeling there was much to be done to make Sound truly feel real to an audience, Shearer expanded his division to perfect sound effects and eliminate camera noise and other studio imperfections. MGM's studios were quickly rebuilt to be sound proof.

Shearer also devised boom microphones, so actors didn't have to stand in one place to be heard. He also revised the way lights were hung and sets built to eliminate any chance still bulky and primitive sound equipment could cast shadows or would otherwise restrict directors when choosing their shots.

Every single one of his alterations to the way films were shot was replicated by the other studios.

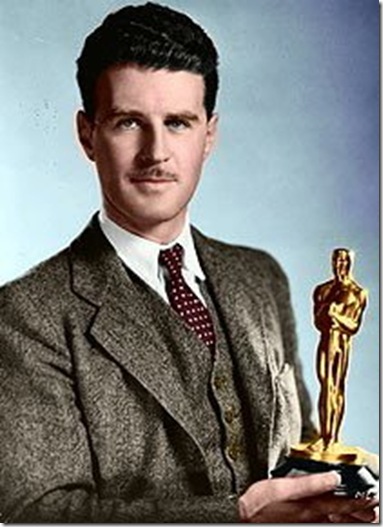

By 1930, there were enough sound films being made for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to award its first Oscar for "Excellence in Sound". Douglas Shearer won for "The Big House", and shared the stage with Norma, who won Best Actress for "The Divorcee", the only time a brother and sister have won the coveted trophy.

But Shearer wasn't content to rest on his laurels. He knew that the main stumbling block to Sound was the theatres themselves, where the era's speakers could not hope to fill their auditoriums. Indeed, sound was so bad in many that Charlie Chaplin continued to release only silent films that regularly topped the industry in box office returns.

Shearer and his team went to work inventing a device that came to be known as "The Shearer Horn". It separated music and dialogue, making both louder and clearer and became the industry standard. His invention remained in use up until the 1970's when theatres converted to stereophonic sound.

For MGM's 1936 film "San Francisco", he invented the first sound "mixer", combining 8 separate tracks of effects, music and dialogue to wow audiences during the movie's climactic earthquake sequence.

And he devised other improvements for film production as well, in 1941 inventing a fine grained film that gave screens in large theatres a never before seen level of clarity.

Then -- Shearer suddenly disappeared from Hollywood.

Never one to attend industry parties or even studio lunches or dinners, he now couldn't even be found in his office or laboratory. MGM ignored all requests regarding his whereabouts.

Then in 1945, he abruptly returned, declining to say where he'd been or what he'd been up to.

Finally, in 1947, he gave an interview to Variety acknowledging that he had spent the war years, at the specific request of President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, perfecting radar. Later, although offered a civilian award for his military service, he declined, insisting he hadn't done it for any glory.

He hadn't done it for money either. During his four years of secret military service, the only paycheck Shearer cashed was the one he got weekly from MGM.

Through the late 1940's and 1950's, Shearer returned to sound recording, winning Oscars for "Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo", "Green Dolphin Street" and "The Great Caruso".

By 1952, he had won 12 Oscars for his achievements in Sound, Special Effects and Technical Achievement, more than anyone else in film history.

But he would add two more to his total before he was through.

In 1958, he went to work developing a wide screen system that would eliminate the imperfect Cinemascope three camera system widely in use. Shearer came up with a 65mm film that could deliver wide screen using only one camera. It was dubbed "Panavision" and was first used on MGM's massive hit and multiple award winning, "Ben-Hur".

For his work, Shearer was awarded another Oscar and garnered his 14th in 1964 for perfecting the process of background projection.

In 1968, Douglas Shearer finally retired and the man no one ever saw lose his temper was asked if he felt slighted for not being acknowledged as the creator of the "Talking Picture". Shearer simply replied, "I knew what the studio and I had achieved and that was all that really mattered".

Douglas Shearer died in 1971, receiving a final honor never before (or since) bestowed on a Hollywood technician. His obituary filled the front page of the New York Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment